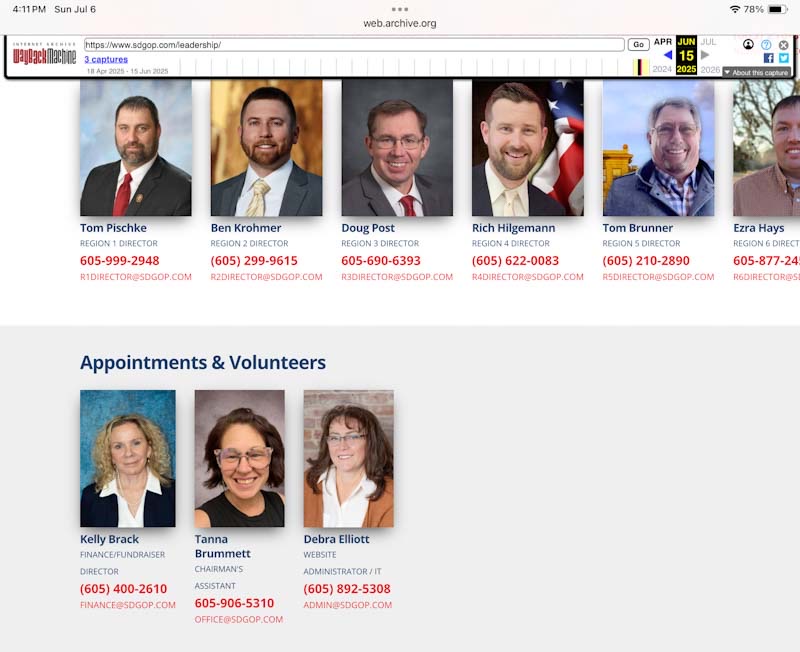

Remember when SDGOP Chairman (& former 32-year Obama Democrat) Jim Eschenbaum claimed “We don’t need any more money thrown to the state GOP than what we need to operate?” (..at the same time he noted they wanted to weed out RINO’s from the party)

I’m thinking that the party might be having some second thoughts about their chairman declaring they don’t need any money. Because it appears that things are looking bad at the SDGOP in terms of what they’re seeing in donations.

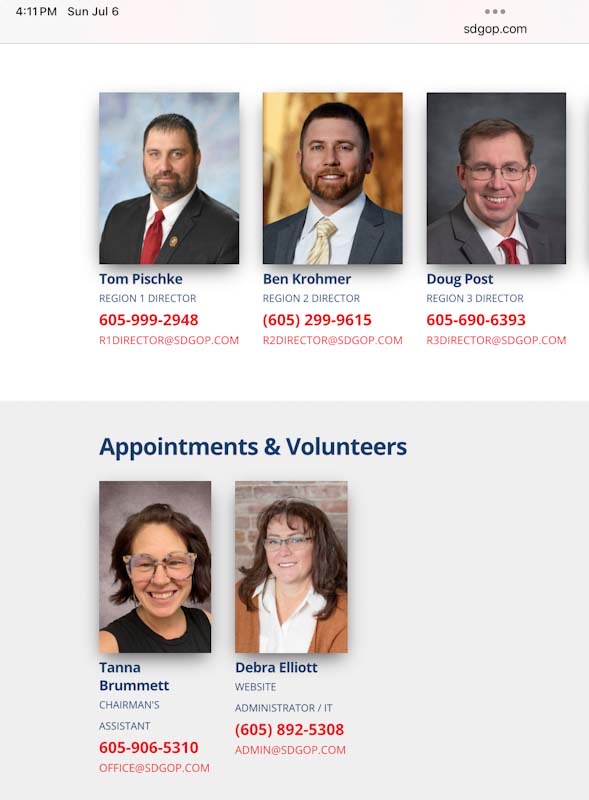

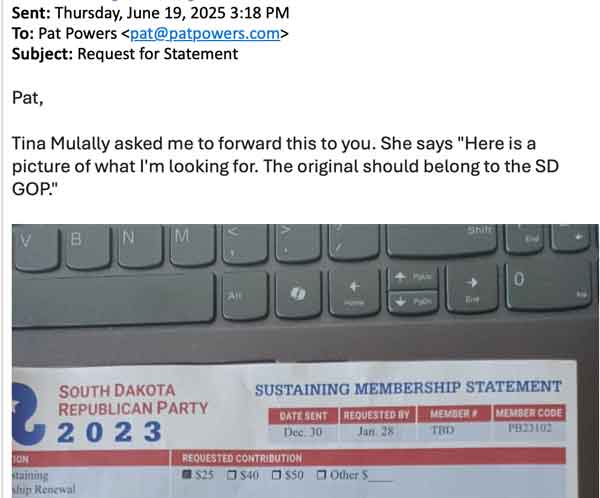

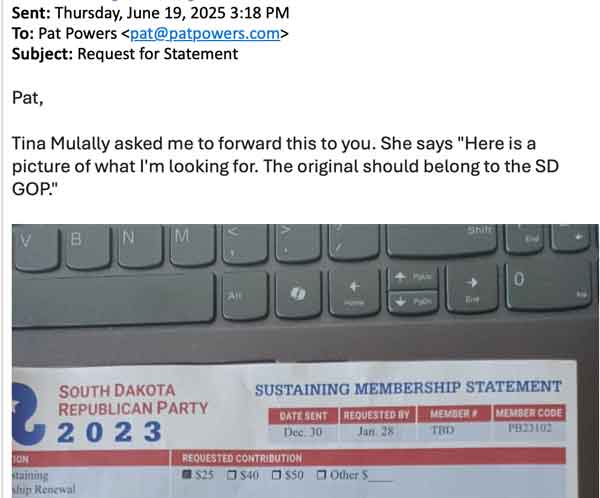

How bad are they getting? Had this note sent to me the other day by the party through an intermediary not long after they filed receiving no donations that month other than from the treasurer on their FEC Report:

Things are so bad that the party actually came crawling to me for something the party put out 2-3 years ago? That’s funny! (You can about guess my reply).

With that as the launching point, yesterday, the SDGOP sent out their proposed budget for the next year, as well as how they’ve done so far in fundraising for 2025:

SDGOP_ExpensesandBudget by Pat Powers on Scribd

So many pie in the sky projections. Has anyone actually done any fundraising before?

I don’t see any expenses for their “Miller Golf Tournament” where they were splitting the proceeds. They actually believe they’re going to take in $30k for a statewide mailer after the previous year the party actually lost money on the last statewide mailer (as I was told) & no line item for postage on that or any other mailer. They think they’re going to raise 25k on a raffle they’re going to sink 15k into, and they’re going to get another $17-18K out of county GOP organizations?

Well. Good luck with that.

Also the party’s finances continue to dim with a notation that as of 6/1, they are down to $29,825.30 in the state account and $26,770.01 in the federal, giving them less than $58,000 total among all their accounts in the face of dwindling finances and few prospects.

Stay tuned, as we find out if the chairman still believes that they “don’t need any more money” a few months from now.

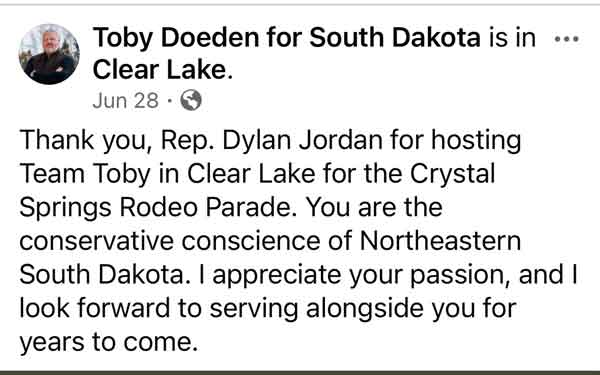

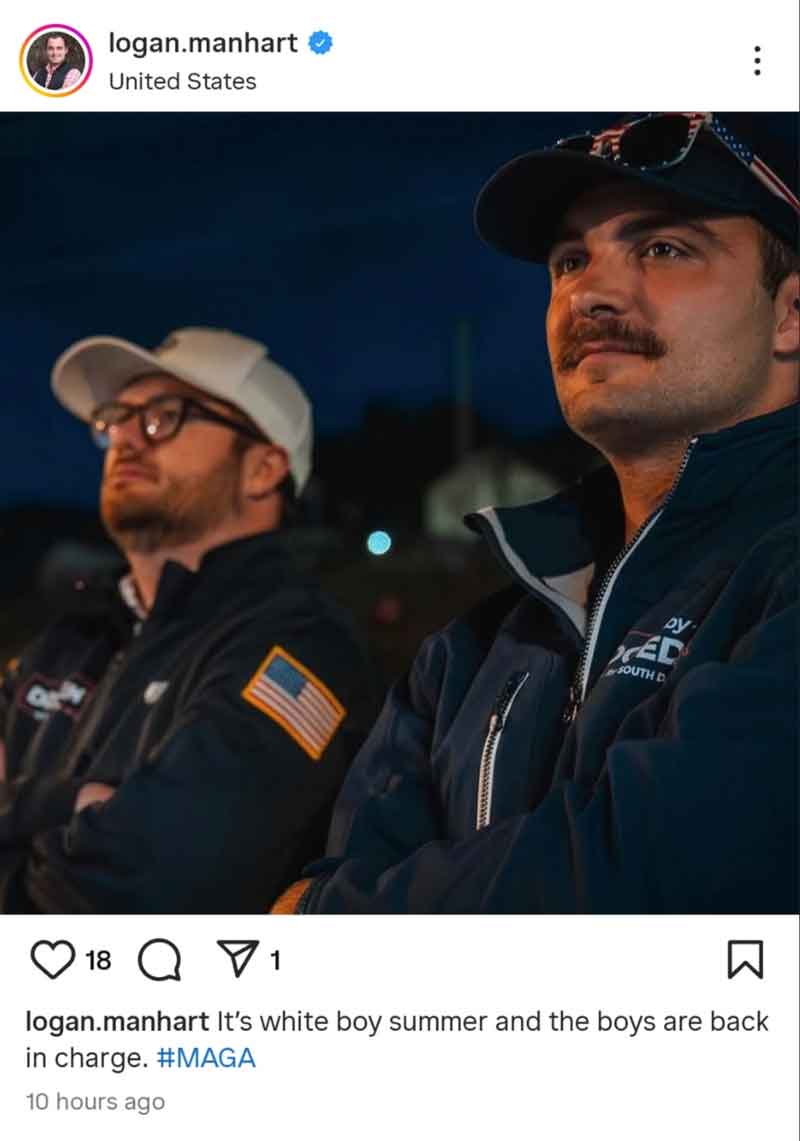

Toby Doeden seems to be confused over what his campaign worker was trying to convey when Logan Manhart was posting about ‘white boy summer’ while wearing his Doeden campaign team jacket:

Toby Doeden seems to be confused over what his campaign worker was trying to convey when Logan Manhart was posting about ‘white boy summer’ while wearing his Doeden campaign team jacket:

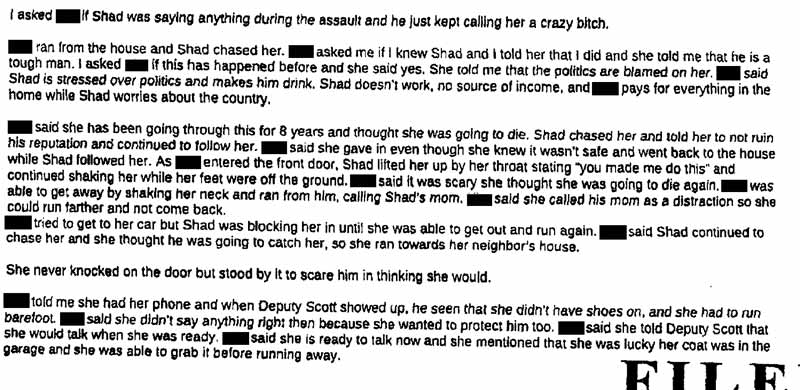

The state was asking for a 180-day suspended jail sentence, and the judge gave Olson a suspended imposition of sentence.

The state was asking for a 180-day suspended jail sentence, and the judge gave Olson a suspended imposition of sentence. As alleged by the girlfriend who managed to escape, 8 years of abuse until his victim managed to escape the cycle of violence.

As alleged by the girlfriend who managed to escape, 8 years of abuse until his victim managed to escape the cycle of violence.